Tiki Barber recently called Adrian Peterson "a liability for his team" due to his propensity to fumble. Is that assessment fair? What if Peterson's fumbles really did hurt his team more than his overall performance helps? Peterson himself admits he has a fumble problem, and he's promised to work on it in the off-season. How many fumbles is too many when it comes to a break-away home-run hitter like Peterson?

Tiki Barber recently called Adrian Peterson "a liability for his team" due to his propensity to fumble. Is that assessment fair? What if Peterson's fumbles really did hurt his team more than his overall performance helps? Peterson himself admits he has a fumble problem, and he's promised to work on it in the off-season. How many fumbles is too many when it comes to a break-away home-run hitter like Peterson?

I'll look at Peterson's fumbles in three contexts. First, I'll look at his rumble rate, which accounts for how often he's asked to carry the ball. Second, I'll look at how costly his fumbles have been in terms of Win Probability Added (WPA). And third, I'll look at his fumbles in terms of Expected Points Added (EPA), which is less sensitive to game situation as WPA.

Aside from his recent fumble problems in the NFC Championship Game, Peterson has committed 4, 9, and 7 regular season fumbles over his three-year career. That's certainly more fumbles than you'd like to see, but keep in mind how often he's asked to carry the ball.

Any fumble is equally likely as any other to result in a turnover or recovery, so I'll start by looking at fumbles rather than fumbles lost. Further, fumble rate is going to tell us more than total fumbles about a player's proclivity to lose the ball. For RBs, especially guys who get a lot of receptions, it makes sense to consider their total touches, which includes carries and receptions.

Fumble rate is extremely random from season to season. For RBs with at least 60 touches in a regular season, fumble rate correlates with the following season at only r=0.04. Fumbles are rare, low frequency events. One or two more or fewer instances in a year can result in an apparently large increase or decrease in fumble rates. Correlations are going to be very low in general, but some guys do show a knack for fumbling.

In 2009, Peterson's seven fumbles came over the course of 357 touches, for a fumble rate of 2.0%. That's one fumble for every 50 touches, and a 50% nominal recovery rate would mean one fumble lost for every 100 touches. His rate in 2008 was 2.3%, and in 2007 it was 1.5%. The league average for RBs with over 60 touches in a season over the last three years is 1.3%, so Peterson has been consistently worse than average.

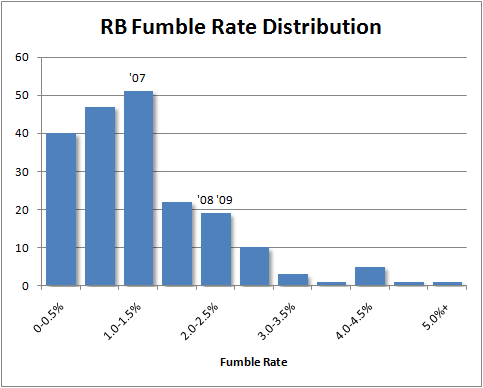

The graph below plots the distribution of RB fumble rates over the past three seasons. In other words, it shows how many RBs fell within each 'bin' of fumble rate. Most backs have a rate between 1.0 and 1.5%, but plenty have more. Each of Peterson's three seasons were within one standard deviation from the mean. Although worse than average, he's far from the league's worst.

Part of the frustration Vikings fans (and fantasy owners) felt with Peterson in 2009 may have to do with the unusually high share of his fumbles that were lost. Six of his seven fumbles in the regular season resulted in turnovers, one of them returned for a touchdown to tie the score. In total, 13 of his 20 career regular season fumbles were lost. But RB fumbles are typically recovered 50% of the time, and recoveries are largely out of the RB's control.

Peterson also seems to have a habit of losing fumbles in critical situations. In his three seasons in the NFL, including playoff games, Peterson accumulated +6.94 Win Probability Added (WPA). In other words, the plays in which he has participated were worth nearly 7 wins above average for the Vikings. Unfortunately, his fumbles, both lost and recovered, have cost -2.42 WPA over the same period, for a net of +4.52 WPA. That's a loss of 35% of his gross productivity due to fumbling.

To put that 35% in perspective, I sampled a few comparable RBs. Chris Johnson has lost 5% of his positive productivity to fumbles. Ray Rice has lost 16%. Michael Tuner and Marion Barber each lost 8%. Clinton Portis came the closest of the group, losing 23% of his productivity to fumbles.

EPA tells a similar story, (but for reasons I'll mention below, we have to take EPA for RBs with a grain of salt). Peterson's fumble-free production totaled +105.9 EPA. For a RB, that's a lot of points above-average over 29 games played. But he has forfeited -76.2 EPA, or about 71% of his gross positive production, to fumbles.

Frankly, 71% sounds astonishing, but it's worth taking a minute to discuss what EPA actually is. EPA is marginal point production above "expected," which is the league-average baseline. It's comparable to a corporation's profit, rather than its overall revenue. Marginal quantities like profits, when compared to the underlying total, are always more sensitive to calculations and comparisons. A doubling of a company's profit may only be due to a 1% increase in its baseline revenue. Both EPA and WPA are sensitive to the same kind of comparisons.

Also, RBs are going to be unfairly penalized by EPA. Due to an apparent fundamental imbalance, running is simply not as productive as passing in terms of Expected Points. Runs on 1st and 2nd down outside the red zone, which comprise the vast majority of rush attempts, tend to be negative events in the eyes of EPA. The average RB is therefore going to have a negative total EPA, and any RB with positive EPA is solidly above average.

But EPA can be even more problematic. According to traditional stats, Peterson's best year was 2008 when he totaled 1,760 rushing yards at a 4.8 Yard Per Carry clip. It's hard to deny that's good, but his EPA that season was actually slightly negative. Fumbles were the main culprit, but there was another drag on his EPA. In games where the Vikings had a lead, he was handed the ball for lots and lots of 1, 2 and 3-yard gains, which are negative plays. WPA may see these carries as neutral or positive because they burn clock, but EPA only sees reductions in the expected net point advantage.

To be fair, we need to compare a RB's EPA to that of other RBs. For example, Ray Rice lost -24.3 of his gross +52.5 career EPA (46%) to fumbles, and Chris Johnson lost -11.1 of his gross +50.0 EPA (22%) to fumbles.

Peterson is not alone as a fumbler, as other great runners have had similar problems. Walter Payton posted a 2.0% fumble rate over his career. Franco Harris fumbled at a whopping 2.8% rate. Tiki Barber was known for his fumble problems, but also for fixing them by the end of his career. Barber's overall career rate was 1.9%, but through the bulk of his career, from 1999 through 2003, his rate was 3.1% (Caution: multiple endpoints argument!). In Barber's final three years, he reduced his rate to 0.9%. Some other notable backs weren't as clumsy: Emmit Smith--1.2%, Edgerrin James--1.3%, Jamal Lewis--1.4%. Brian Westbrook is the counter-example, with an enviable 0.7% career fumble rate. (Historical data from PFR.)

So, yes, Adrian Peterson does have a fumble problem, but much of it has to do with the situational context in which his fumbles were lost. If Peterson could control when they were lost, I'm sure he'd choose to fumble only when it wouldn't matter. But he obviously can't do that. All he can do is improve his fundamental techniques to reduce his overall likelihood of fumbling.

The real question is: given his costly fumbles, is he a liability? According to WPA, he's not. Theoretically, the average RB would net slightly below 0.0 WPA. Peterson's career net +4.52 WPA means he's been a net positive in helping his team win. Fewer turnovers would be nice, and although it must be frustrating to teammates and fans alike, even if Peterson doesn't improve his fumble rate he's still worth it. Still, imagine how valuable he'd be if he could reduce the fumbles.

Isn't using Fumbles/Touch a little flawed. I assume RB's fumble less on receptions so that makes RB's who are main options in the passing game look better (EX: Ray Rice). Shouldn't you adjust for that?

also, I'm not sure why included Michael Westbrook in this sample. He's a WR.

I meant Brian. I do that all the time.

Yes, touches is a little flawed, but probably a lot less flawed that looking at carries alone.

Are these stats normalized in anyway to account for 'strength of schedule' or basically what defenses teams are going up against?

It seems to me that while AP is worth having, fumbles and all, his fumbles cut down his value quite a bit. His overall production is not that of an elite RB, when fumbles are taken into acconut. Keep him, yes, but he's no superstar - as long as he fumbles like he does.

You can't really compare modern fumble rates to those of Payton and Harris (and others from the 80's and earlier). P-F-R had a blog post a few years back on this, but fumble rate now is less than half what it was in 1980. This is likely due to instant replay (until this season, instant replay could only remove fumbles, not add them).

I also think that fumbling now is much worse than fumbling then. As you've pointed out, one main reason for running the ball, besides game theory, is that it's much less variable than passing. Turnovers lead to more variation, so if a goal of the running game is safe, consistent gains, fumbles are an awful thing.

Contrast to 25+ years ago, when the running game was roughly as effective as passing in gaining yardage. Then, you could deal with more fumbles, since you weren't running to be more consistent and safe, but rather to gain yardage.

Eddo-That's true. I suspected that, but didn't have the historical numbers. If anyone has the PFR link, that would be great.

Also, to answer the question above, no these numbers don't have adjustments for opponents.

Maybe he is valuable overall, but to link this article with the underdog/favorite one, a top team like the Vikes probably need more a steady, low variance back than a boom and bust back.

Here's the post I wrote a couple of years ago:

http://www.pro-football-reference.com/blog/?p=522

To correct Eddo's recollection, I suspected instant replay was a cause, but when we compare the years that replay was introduced, then removed, then re-introduced, we don't see any spikes that would suggest they were a huge factor. Fumble rates for running backs have been consistently declining since the 70's.

My theory was that the increase in passing efficiency has led to decreased fumble rates, because fumbling is less tolerated if passing becomes safer and more efficient. It would take an explosive player like Peterson to be an exception, because if he was mediocre and he fumbled, he would be replaced.

Another example this year is Jamaal Charles. His reputation as a fumbler is what kept him on the bench. Even when Johnson was suspended/released, they initially wanted to give the ball to a more sure handed but way less explosive Kolby Smith. It took several games (and a bad passing offense) for Charles to get his chance and run with it. If he was with Indianapolis instead of KC, I suspect he may not get that chance. You don't take the ball out of Peyton's hands--and we don't care if you can break the occasional 50 yard touchdown.

Thanks, Jason. Maybe the distribution graph above supports your notion. There is an unnatural drop-off in the number of RB's with fumble rates > 1.5%. There's a big survivorship mechanism at work. As soon as a guy starts fumbling more than average, he's on the bench or cut, and no longer in the sample.

Brian - does your data allow you to tell when a runningback has run out of bounds rather than take the hit?

Merely hypothesizing here (I don't have the data to hand) but is it possible that a RB may appear to have a high fumble rate because they choose to stay in bounds and fight for more yardage when they find themselves outside?

It might well be that Peterson doesn't have poor technique, but instead he goes after the defender versus taking the safe option. Of course, then it doesn't mean he can't improve, just that he'd need to think more about his game.

Sometimes, but not consistently. It's the same data you can pull off nfl.com. Most official scorekeepers will say 'pushed ob (M.Tackler),' but not always.

I was saying the same thing yesterday. Running ob rarely results in a fumble, and the few fumbles that do occur are almost never lost. Peterson does have a reputation for taking guys on. He claims guys are afraid of tackling him, so they just go for the strip. I think that's farcical, but it is revealing of how he thinks and how he takes on tacklers.

Just read Jason's post at PFR. Wow. Fumble rates have really come down, far more than I would have imagined. I should probably delete the stuff about W.Payton and F.Harris in the final draft (after I'm properly embarrassed).

Brian, did you ever consider possibly using a Poisson distribution for modeling fumbles? Since fumbles themselves are pretty rare events, a Poisson might be better.

Also, have you considered trying to put together a group of RB's that run ob more than others do? You might have to establish some arbitrary cutoff and it could turn into a multiple endpoints argument but it'd still be interesting to play around with.

Thought about posting this on PFR, but didn't want to be a year and a half late to the party. My first thought when I read Eddo saying that fumble rates have declined is that defenders are having to make more tackles in space. Making a solo tackle in space is hard enough without thinking about the strip. As a sam linebacker in high school, I was coached to go for the srip if I was the second defender to meet a ball-carrier in traffic, but in space my responsibility was only to finish the tackle.

Just curious if fumble rates are different for indoor games than they are for outdoor games.

Also, a slight suggestion for your profits/revenue analysis. I would compare EPA to economic profits rather than accounting profits since both take into account expected production. Taking expected production into account makes the value even more sensitive.

I'd be interested to know where Barry Sanders sits in the comparison

I think one point that is more football and less statistics regarding AP's fumbling problem is the tenacity of his running style and his stubbornness to go to the ground. Peterson seems to sometimes relish contact when carrying the ball often getting stood up by two or three defenders before going down. The propensity to fumble after contact must increase. The propensity to fumble after contact with multiple defenders must skyrocket.

He seems to be playing the Franco Harris card, scratching and clawing for every yard but risking putting the ball on the turf, rather than the Emmit Smith card, conservative and efficient running that may not be as explosive but yields fewer fumbles.

Just a thought...

Just a thought:

It might be worthwhile to look at where each fumble occurred. It seems to me that a great runner like Peterson loses more fumbles because the average runner loses it around the line of scrimmage, where he gets hit the most (and where there are a lot of O-linemen standing around to recover it). Peterson, I'm guessing, loses a lot of fumbles downfield, after breaking into the open and getting hit 10-20 yards downfield, and often in the middle of the field, where I'd imagine there would be a much smaller chance of a recovery by the offense, given how many defenders are around the ballcarrier at that point. Could explain why his fumbles lost % is higher than 50%.

@Most recent anonymous: Didn't Harris have a reputation for avoiding contact? A better example of a runner taking punishment would be Earl Campbell or Walter Payton, I would think.

@Ryan: We're not just talking about lost fumbles, though; we're talking about all fumbles.

There are no guarantees in the NFL. A team could be great one year and suck the next because of injury, player/coach changes, etc. Peterson's fumbles might be more costly than just a few points or loss. Surely there's some sort of opportunity lost cost. How many more times will his team get into the playoffs?

The next step seems to be then examining what Adrian Peteron's annual salary is, and comparing his net WPA and EPA with the rest of the league's active running backs. He may still net out out positive gains, but is that gain offset by the salary cap hit he represents for the Vikings team each year?

Wondering if there is any statistical data connecting fumbles to winning percentage of teams?

help?

thank you,

High&Tight