Navy plays a triple option offense, a somewhat rare scheme even in college these days. The triple option allows Navy to compete against much bigger and faster opponents using discipline and execution as their weapons. They tend to be at or near the top of all Division I (FBS) schools in running every year, partly because they rarely pass and partly because they run the option so well.

Navy plays a triple option offense, a somewhat rare scheme even in college these days. The triple option allows Navy to compete against much bigger and faster opponents using discipline and execution as their weapons. They tend to be at or near the top of all Division I (FBS) schools in running every year, partly because they rarely pass and partly because they run the option so well.

Navy has enjoyed tremendous success in recent years, especially for a school that offers its recruits a rigorous and austere lifestyle, an extremely challenging curriculum, and virtually no chance of an NFL career. Last year they won 10 games, including their second win over Notre Dame in three years and a 35-13 drubbing of Missouri in the Texas Bowl. It was their seventh consecutive winning season and seventh consecutive bowl appearance. QB Ricky Dobbs broke Tim Tebow's record for rushing TDs by a QB last season. As my favorite Navy blog put it, archrival Army looked at their two-touchdown loss to the Midshipmen last year as a cause for optimism.

One thing about option football is that there is always a very good chance of a gain of at least a few yards. There aren't sacks or incomplete pass attempts. Navy always seems to be able to gain at least 2 or 3 yards when they need to, even when the defense knows exactly what is coming.

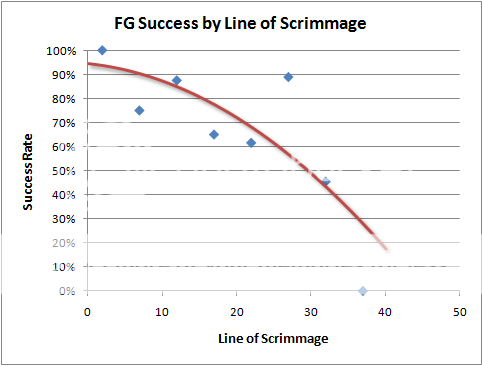

I'll use the same methodology I used in this analysis for NFL 4th downs. In short, I'll look at each distance to go at each yard line on the field. I'll compare the Expected Point (EP) value of going for the conversion with the EP values of punting and attempting a field goal. The EP value of the conversion attempt is based on the EP value of a first down at the marker and the EP value of turning the ball over on downs at the line of scrimmage, weighted according to the likelihood of conversion.

For this analysis, however, I'll use statistics only from recent games against BCS opponents. As an Independent, Navy plays a wide variety of opponents. This includes opponents such as Notre Dame, Boston College, Stanford, Cal, Ohio St., Maryland, Pitt, and many other competitive programs. Games from 2002-2009 are included in the analysis.

Looking at only one team's games restricts the data greatly compared to my NFL study. Restricting the data further to only BCS opponents means that I'll need to smooth the data points to fill in the gaps. We'll start by looking at Navy's EP curve for 1st downs.

The first thing that stood out to me was how flat the curve is compared to the NFL. This makes sense because college teams tend to score easier and quicker. The graph basically says that simply having possession is highly valuable because it's going to frequently lead to points.

The flip side of this curve is that your opponent is also more likely to score when he has possession. And when your opponent is stronger than your team, it means the curve is going to be even higher. Navy's BCS opponent's EP curve looks like this:

The next thing to consider is Navy's estimated conversion rates for various distances to go. Unlike the NFL analysis, there was not enough data to break out different conversion rates for various parts of the field. One thing to note is that there is very little difference in success rates for between BCS opponents and the others. As I've mentioned in previous articles, the difference between very good and very bad teams one one particular play is minuscule. It's only when those differences compound over an entire game that we can tell the good teams from the bad.

One other difference from my NFL analysis is that I measured the EP value of punts directly instead of estimating the net punt distance, then using the EP value of a 1st down at that location. The advantage of the direct method accounts for potential blocks, turnovers, and penalties. Here is the EP curve for Navy's punts:

For each distance to go, at every yard line, we can compare the EP value for the three options: go for it, FG, and punt. The option with the highest EP is the recommended choice:

To be honest, I was surprised by this result. I had expected that a FG attempt should only be the favored option at extremely long to go distances. I think Navy's lack of a medium-to-deep passing threat makes 4th and long a very difficult conversion. But given that Navy typically runs on 1st and 2nd down, 3rd and long situations are relatively uncommon, penalties not withstanding.

Ultimately, their reliable option running game makes it worthwhile for Navy to go for it in far more situations than they typically do.

Brilliant work, Brian. I enjoy this type of analysis most of all.

Has Niumatalolo called to ask you to consult yet?

That's very interesting. I would never have guessed it to be advisable for any team to go for it on 4th and 7 regardless of field position. It would also be interesting to run a run vs. pass analysis as it applies to Navy given their lackluster passing ability. Thanks for all the work you do.

I would take into consideration that it is easier to convert 4th and long at mid-field then 4th and long in the red zone. Both are passing downs, but the field is compressed on 4th and goal situations. Also, going on 4th and long distances is often a strategy late in the game and often defenses are in prevent mode. Finally, the 4th and goal often stirs the emotion of the defense, making it more difficult than in 4th downs in other situations. Anyway, for this analysis to guide a strategy that produce results, it has to be in a situation where it matters, so the defense is going to rise to the occasion. Very interesting analysis though. Offensive coordinators need to know these probabilities, but it should not hinder tactical trickery.

Awesome article. I love the use of the fourth down chart to a single team. If I were a head coach, I would hire you to create one for my team.

I have been waiting a long time for a "conservative" running team to figure out the enormous advantage of consistently going for it on fourth-and-short. It means that teams only need to average 2.5 yards per carry to consistently drive down the field. For a dominant running game like Navy or Georgia Tech or Nevada, etc, this is no problem.

I hope that head coaches finally figure out the benefits of this strategy.

As an aside note, I read somewhere that Navy did a statistical analysis of a minimum frequency that a team needs to pass in order to force the defense to respect the pass and not play 9+ in the box. Apparently, they came up with the 20% figure (i.e. you have to pass 20% of the time and run 80% of the time).

Is it possible to recreate this analysis. I think it would fit in nicely with your other game theory analysis.