I’ve been writing a lot about run-pass balance lately, and part of my theory of why teams are perhaps passing less often than they should has to do with the evolution of the sport. Rule changes over the recent decades have generally favored passing. Changes in pass blocking rules and in pass interference rules have made it easier to pass the ball successfully. Even subtle rule changes such as the definition of possession and “control” may have made receiver fumbles less likely.

I’ve been writing a lot about run-pass balance lately, and part of my theory of why teams are perhaps passing less often than they should has to do with the evolution of the sport. Rule changes over the recent decades have generally favored passing. Changes in pass blocking rules and in pass interference rules have made it easier to pass the ball successfully. Even subtle rule changes such as the definition of possession and “control” may have made receiver fumbles less likely.

Tactics and play selection have been refined over the years to take advantage of the rule changes, but I’m not sure that they’ve completely caught up. Results from several studies, including my own, have suggested that in most situations, passing is more lucrative than running. This imbalance implies that passing should be selected more often. As defenses respond to expect more frequent passing, the payoff for passes will decrease as the payoff for runs increases. Eventually, there is an equilibrium where the payoffs should be equal.

In this post, I’m going to look at very simple historical trends. As you’ll see in the graphs below, there is evidence that the current run-pass balance has not responded fully to recent increases in the payoff of passes. All data come from PFR's very cool league historical pages.

The first graph charts the yards per play for running and passing over the past 60 seasons. Without detailed play-by-play data, we can't rely on advanced metrics like Expected Points Added (EPA). Instead, simple efficiency will have to do. The passing efficiency I used is Adjusted Net Yards Per Attempt (Adj Net YPA). 'Net' means that sacks and sack yards lost are factored in, and 'Adjusted' means that there is a 45 yard penalty for every interception. The running efficiency I used is straight-up Yards Per Carry (YPC).

You can see the dramatic increase in passing efficiency following the 1978 rules changes. I was familiar with that increase, but what I wasn't aware of was the steep decline in passing efficiency during the '60s. As early as 1961, passing efficiency was nearly as high as it was throughout the '80s, during the Bill Walsh/West Coast Offense trend. In contrast, running efficiency has been remarkably steady, hovering around 4 YPC since the end of World War II. (I think that before then, sacks were considered rushing losses, which would explain the uptick in running efficiency in the late '40s.)

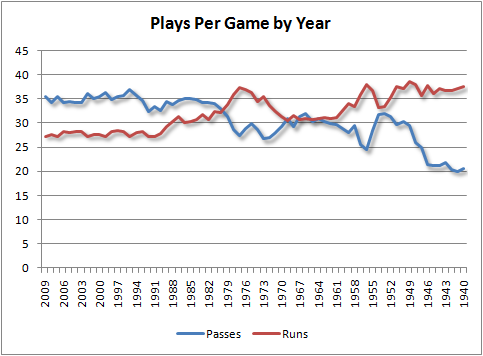

The second graph charts the number of runs and passes per game by year. We need to look at it on a per game basis because the number of games in a season has changed over the years.

You can see that the proportion of passes declines following the '60s in response to the decline in efficiency. Then there is a jump in the proportion of passes following the 1978 rules changes. It took several years for the balance to fully shift. There was a lag as coaches realized the new potency of passing.

Now look at the more recent years. Following 1984, when the increase in passing efficiency leveled off, it soon began a slow but steady climb to where it is today. But also notice there has been no corresponding increase in the proportion of passing. In 1984, passing efficiency was 5.0 Adj Net YPA, and running efficiency was 4.0 YPC, for a net passing premium of 1.0 yards per play. By 2009, passing efficiency climbed to 5.6 Adj Net YPA, while running efficiency was 4.2 YPC, for a premium of 1.4 yards per play. That's a 40% increase in the premium.

In 1984, passes represented 54% of all plays. By 2009, the proportion of passes climbed only to 56%. That's a relatively meager increase, barely above the noise of random year-to-year variation.

Here's what I think is going on: Coaches took several years to fully take advantage of the increase in passing's effectiveness following 1978, and that increase was obvious and immediate. The more recent and more subtle increase has yet to be realized. Passing, in most situations, has become more productive, but coaches haven't taken advantage of it yet.

Further, from a game theory perspective, the rock-solid steadiness of running efficiency is very surprising to say the least. If the '78 rules changes suddenly increased the effectiveness of passing, we would expect a corresponding increase in the proportion of passing, which we do see. But we'd also expect to see an increase in running efficiency as defenses adjust their schemes to counter the new realities of passing. But it's just not there.

To me, this suggests defenses have largely remained unchanged, despite the focus on pass rushing beginning with players like Lawrence Taylor. Defenses appear to stubbornly focus on the run, making certain that they keep running efficiency under control. But this focus comes at the expense of passing efficiency. Defenses are happy to let passing efficiency 'be what it will be' in their pursuit of stopping the run.

Defenses may not have a choice. Perhaps once running efficiency gets much over 4 YPC, stopping an offense becomes extremely difficult. With 3 tries to get 10 yards, perhaps 4 YPC is a magic number that the basic rules of football dictate. It could be that run defense is simply inelastic. The way modern defensive schemes are constructed, defenses are unable to shift toward stopping passes more effectively. Whatever the reason, defenses appear either unable or unwilling to adapt.

If this is true, there is little doubt that offenses should take better advantage of the current imbalance by passing more often, specifically on first and second down outside the red zone. Offenses should force defenses to respect the pass more and more until they respond, thus allowing runs to become more productive. If defenses are unable to respond, it's possible that passing in certain situations has become a 'dominant strategy.' In game theory terms, this would mean it never makes sense to run. I doubt this is the case, but if defenses are truly inelastic, that's what it would mean.

Interesting stuff. I can't believe how steady rushing has been throughout the Superbowl era.

Do you think part of the defensive strategy focuses on the low v high variance results? Rushing is a lower variance play than passing, and so for the defense it is important to ensure that a team cannot use a low variance outcome to march up the field. In other words, you have more chance of forcing a team to punt if you force them to use a boom-or-bust style offense than a constant-grind one. Using a simple example, if an offense can rush for 4 yards every play then you'll never get them off the field, but if the offense passes for 12 yards on 50% of the plays and incomplete the other 50%, then you've got a 12.5% chance of stopping the drive each first down. You'd rather give up the 6 yards per pass play than 4 yards per rush because of the variance.

Given that the sensible option is to allow as much rushing as you can up to the limit of rushing being guaranteed first-downs, it would seem that an average of 4 yards per rush is the historical limit that makes teams pass. If you sold out more on stopping the pass then perhaps the offense would just switch to the low-variance choice.

Ian,

4 yards per run is the same boom-or-bust style as passing: 3 things can happen on a run, 2 of them are negativ (fumble, minus-or 0 Yard-Gains). Efficient Passing is impossible to stop. It always was, always will be. Every year winning teams are also very high in the rankings of Y/PP, while teams with high Y/R have no influence of winning. Thats why great offenses always were efficient passing offenses (for examples: Rams 50s, Chargers 60s, Steelers 70s, 49ers 80s, Cowboys 90s, Rams early 2000s, Indy/NE lately).

Since Unitas, the NFL-Winning-Formula is to built a lead with efficient passing, and run down the clock after.

The same is true with efficient defenses, if you stop the pass you win, if you stop the run, it does not matter*.

* = ONLY the Ravens 2000 won with that style, but then again, Dilfer was also highly efficient in the post season ...

Karl from Germany

Karl

Yes, but as it's no secret that they are great passing teams then why don't opposing defenses sell out more to stop the pass? This is what Brian is saying. Passing nets more yardage on average, so why don't a) offenses pass more and b) defenses play to stop the pass more? Game theory suggests that there should never be 'great passing teams', as defenses ought to adjust to those teams that gains loads of yards passing, such that rushing and passing give up equal yardage and leaving us with 'great general offense teams'. As this is not what we see in practise, there must be a good reason for defenses to choose to over-defend the run.

I was hypothesising that as rushing is a lower-variance option than passing, defensive coordinators, when faced with great passing teams, choose to make them pass rather than over-defend the pass and make them rush.

"Game theory suggests that there should never be 'great passing teams', as defenses ought to adjust to those teams that gain loads of yards passing, such that rushing and passing give up equal yardage and leaving us with 'great general offense teams'."

Ummm, not quite. Game theory predicts the eventual discovery of a minimax solution (i.e., a "Nash Equilibrium"). The Nash Equilibrium does NOT infer that both options (pass or run) will eventually yield equal results.

In the case of football, there should be a minimax solution available that will yield the offense the maximum number of yards per game. The minimax solution will almost certainly NOT yield equal rushing and passing yards.

Most "equilibriums" consist of a mix that, at first glance, looks to be unbalanced. For example, maybe the "perfect" balance of pass-to-rush is 70/30. This implies that if the offense starts to pass more than 70% of the time they will, in the long run, gain fewer yards and if the offense starts to run more than 30% of the time they will, in the long run, gain fewer yards. This would be a "Nash Equilibrium" solution, even though the two options of pass and run are not equal.

Alchemist

I don't get it. If the payoffs between pass and run were not equal (let's say I have a pass/rush ratio of 70:30, and passing gains me more yardage) why not pass more?

As an example. Let's say my offense gains 10 yards per pass and 2 yards per rush when I operate with 60% passes, and 6 yards per pass/5 yards per rush at 70% passes. Obviously, in the first case my average play length is higher (6.8 to 5.7). Is this your point?

I think it's safer to say that game theory predicts that we'd never detect great passing defenses, not that there won't be great passing defenses. In theory, teams that have great pass D should adapt to focus on the run, equalizing payoffs from both play types and therefore minimizing overall gains by the offense.

*But* the variance issue is important:

Take an extreme case. Presume for the sake of argument that runs always gained exactly 3.5 yds every play. You'd score a touchdown on every drive.

Now assume passing gets you 10 yds 50% of the time and it gets you 0 yds the other 50%, for an average of 5.0 YPA. There's a premium of 1.5 yds in favor of passing.

But, there will be plenty of series where if you pass at least once you won't get a first down. If you have an incompletion on 1st down, now you need 2 consecutive completions to avoid a 4th down.

It's an extreme case, but an example of why low-variance consistency can be good despite the lower overall expected gain. The structural rules of football may favor low variance. That's kind of what I was getting at when I said 4 YPC may be a 'magic number.'

The other research based on Expected Points will account for all the variance--sacks, turnovers, incompletions, etc.--because EPA takes into account future expected net point gain, not just the immediate yardage result of the play in question.

I should also point out (to head off any comments to the contrary) that I'm *not* expecting overall run and pass efficiency to be equal.

What I'm looking for here is the relative increase or decrease in run and pass effectiveness over time. And in particular, I'm looking for a corresponding response in the proportion of the play type with the increasing effectiveness.

"I don't get it. If the payoffs between pass and run were not equal (let's say I have a pass/rush ratio of 70:30, and passing gains me more yardage) why not pass more?"

The best way to illustrate this is simply to take it to its logical extreme. If I gain, on average, 8 yards for every pass and 4 yards for every run, then why even run at all? Won't I make twice as many yards per game if I just pass on every single down?

Of course, the answer is "no". The system is dynamic and the equilibrium is not simply between the choice of pass or run, but more distinctly between the strategies of offense and defense.

If an offense never ran the ball, that offense's pass efficiency would probably drop quite severely because the defense could sellout to stop the pass. And the same works in converse - no matter how good your running attack is, you probably can't get away with running on EVERY play.

Alchemist

Thanks. I think it's falling into place (either it's just me, or this is actually one of those cases where logic tells you one thing and the truth is different).

So, if passing gains more yards one CAN say "well then pass more". BUT, by passing more you're affecting the pass/run balance and so your base changes. As you say, if my current balance is 50/50 and passing outgains rushes then why should I ever run? But it's physically impossible to pass every play when your P:R balance is 50/50, so my question is actually illogical. This is a lot to take in on a Friday evening.

Brian - thanks for clarifying that you're not looking for equal gains on pass and run plays.

Did I at least get one thing right earlier though? An important point is the variance, and it actually seems that teams play the best pass defense they can that limits the offense to 4 yards per carry on rush plays, presumably as any more skew to the pass would mean the low variance on run plays gives the offense too much probability of gaining a first down with little risk.

Yes. That's a good way to put it--defenses appear to defend against the pass as best they can while holding the run to 4 YPC.

"Ummm, not quite. Game theory predicts the eventual discovery of a minimax solution (i.e., a "Nash Equilibrium")."

That's not true. That's only true in a simple, finite zero-sum game, which football absolutely isn't - at the very least, it's a repeated game, and since it's a stateful game, it's at the very least a stochastic game. It's also a stochastic game with imperfect information, and one with an unknown length since teams (in the beginning) don't know how long the game will last.

There's really no reason to believe that minimax for both players would be a Nash equilibrium, especially considering the two players aren't equal, since the offense can choose what information it gains from a play.

In other words, it could easily be that the "best" playcalling strategy is one which gains a good amount of yardage/field position/etc. *and* a decent amount of information/play (on offense) and prevents yardage/field position/etc. while *not* revealing a lot of information/play (on defense). Sacrificing a small amount of yardage to gain/protect information about defensive behavior seems completely reasonable.

From a "theoretical" point of view the reason why minimax isn't necessarily ideal in this kind of a game is because you're doing more than just maximizing your payoff in each stage - you're also learning the 'rules of the game,' so to speak.

In this situation, you would naturally tend to play 'safer' plays more often to feel out a defense with less risk.

"I don't get it. If the payoffs between pass and run were not equal (let's say I have a pass/rush ratio of 70:30, and passing gains me more yardage) why not pass more?"

Because you know, either from knowledge of the defense's behavior or prior attempts at trying, that passing more will decline the effectiveness of passing enough so that the total average effectiveness is less, either immediately, or as the game goes on. (Think of it as "using up your bag of tricks").

The *entire argument* for "you should pass more, because running is so much less effective" is that passing more would force defenses to play pass more, and thus would raise the ypc of rushing, and lowering the ypa for passing.

But what if defenses are *already* playing pass as good as they possibly can? In that case, the decreased effectiveness from passing more would come from some other effective - possibly faster play recognition from the defensive players, or offensive player exhaustion.

Pat-You're off on a contrarian semantic tangent throwing up strawmen.

Why do you think there hasn't been a response in the proportion of passing despite the recent long trend of increasing efficiency? There was a response after '78. There was a response after the decline in the 60s.

"So, if passing gains more yards one CAN say "well then pass more". BUT, by passing more you're affecting the pass/run balance and so your base changes."

More accurately, by passing more, you're affecting the way the defense plays (or at least you should be, assuming that the defense is any good). That's why I said it's a dynamic system. As you change your strategy, the strategy of the opponent adjusts in an attempt to counteract yours.

If all you do is pass, then the defense would almost certainly react in such a way that your passing efficiency drops precipitously because the defense wouldn't care about the run and would devote all of its energy to only stopping the pass.

I'll admit I haven't read most of the article or any of the posts, but I've been wondering something for a while: what more can the defense do to stop the pass?

Stopping the run seems easy: bring an extra player or two into the box and overwhelm the offense with numbers. To stop the pass, what do you do besides get better players... drop an extra man into coverage? Blitz more? Double-team more? All of those have major weaknesses in no pressure on QB, quick throws can turn into big gains, leaves someone else open. One way I can think of is to trick the QB into making the wrong read (zone blitz, DB shows blitz but bails, etc.), but even that doesn't work against the best QBs.

The idea that offers the best hope in my mind is the "Times Square Defense" (as TMQ calls it) the Steelers and other teams use, because you have no idea who is going to do what, making a pre-snap read nearly impossible.

I realize I'm beginning to ramble, it's a bit off-topic, and Brian's point is eventually the defenses will be forced to come up with new innovations that balance out the different options. But what if it's simply not possible for passing and running to balance out?

Good question. I'm not a defensive coordinator, and I don't know if these are realistic, but here are a couple thoughts from a guy whose 8-yr old beats him in Madden.

-You could play nickel or dime defense on what are now considered running downs. You could replace some of the big def tackles with faster pass-rush specialists.

-You could periodically have some pass rushers sell out their gap and ignore the run.

-You could replace some LB-type defenders with SS-type defenders.

I think they would be able to do it because teams do (roughly) equalize running success and passing success based on the expected proportion of each and the to-go distance on 3rd down. See this article on 3rd down conversion percentage.

Actually teams not only should pass more, they should pass ALL the time (if they have a good OL and/or QB). It´s impossible to stop efficient passing unless you have a great great Pass-Defense with the help of luck (speak interceptions).

I don´t know what Nash equilibrium etc. is, but i think it´s not needed. Because people seem to forget that you have different types of passing (short slants, dump offs etc. vs. prevent defense; deep routes vs. blitzing defenses; etc.).

3 examples where Teams did pass all the time (so they were PREDICTABLE) and still could not be stopped:

http://www.nfl.com/liveupdate/gamecenter/26951/IND_Gamebook.pdf

http://www.nfl.com/liveupdate/gamecenter/17741/DET_Gamebook.pdf

http://www.usatoday.com/sports/nfl/super/superbowl-xxxiv-plays.htm

The only "medicine" against good offenses (speak "Pass-Offenses") is either a.) to have a great Pass-Defense or b.) (if you don´t have a great Pass-Defense) you MUST try your luck in a Shoot-Out.

Karl from Germany

I think stopping the pass has everything to do with the type of players you have on defense. Smaller, quicker players are better at stopping the pass than bigger, slower player. First of all, smaller defensive lineman tend to be better pass rushers and also small defensive backs (to a point) are better in pass coverage.

I think the prime example of a team that is built to stop the pass is the Indianapolis Colts. If your defense is built to stop the run, then it will be difficult to change strategies to stop the pass in the middle of a game. However, since the NFL is clearly a passing league now, I think more defenses will be built like the Colts.

Looking at the data on a per game basis misses two parts of the answer. First, the defense is geared to put the offense into 3rd and long, when the offense is more predictible and more easily stopped. If you stop the run on 1st and/or 2nd down, you change stack the 3rd down pass vs run call to favor the defense.

This is also plays role in passing on 1st and 2nd down being more successful.

The second piece is the ability to control the time remaining. If you can't stop the run, you have fewer chances to get the ball. If you can't run the ball, you give additiional tries to your opponent (see 2005 Steelers vs 2009 Steelers.)

In short, referrence your run/pass by down articles.

"You're off on a contrarian semantic tangent throwing up strawmen."

Which one's a strawman? Each possibility is supported by both game theory and actual evidence from football coaches when they explain playcalling.

Passing has been more successful than rushing since 1978, when the rules dramatically changed. That's 31 years.

If there was a more successful playcalling strategy available, it's highly unlikely no one would've found it in 31 years. They started to adapt to a newer, better strategy that had become available nearly immediately in 1978. The lag that you mentioned before 'modern' efficiency was hit was about 10 years. It's been twice that now.

It is far, far more likely at this point that there's some basic feature of the game that discourages more extreme levels of passing.

"Why do you think there hasn't been a response in the proportion of passing despite the recent long trend of increasing efficiency? There was a response after '78. There was a response after the decline in the 60s."

I've offered several possibilities.

1) Passing more simply isn't realistically possible due to fatigue. This has some intuitive support, since passing plays cover much larger distance than running plays.

2) Successful passing requires determining a defense's weakness, which is best done via safer plays. This is supported by statements from coaches.

3) Successful playcalling requires manipulating defensive player actions, and runs manipulate defenses in ways that other passes cannot.

It's important to state that it's hard to prove any of these statements, as they would be *beliefs* of coaches rather than facts. But I don't see why it's any less likely than the belief that teams would do better if they passed more.

There are other interesting possibilities as well. Coaches could be optimizing for something other than gain per play - with football being such a low-scoring game, it's possible that average results would just require too long of a game for the best strategy to win out.

Geh, missed the support of #3. That's supported by the fact that runs are the only plays where offensive linemen can immediately move downfield.

Also #1 would also be supported with fatigue/injury to the quarterback as well.

More strawmen. You didn't answer the question, kid. Why no response?

1) I haven't been a kid in a very long time.

2) A strawman is an example based on a misunderstanding (or misrepresentation) of the original position. Your position is that "eventually, there is an equilibrium where the payoffs [for run and pass] should be equal." I gave several examples where this would not be the case. That's not a straw man. You might believe the examples are ridiculous, although I've given support for the basic idea, but that still wouldn't be a straw man.

The previous changes - in the late 70s and in the 60s - might not be comparable, because in both of those cases the trend was either towards more balanced playcalling (i.e. the *infrequent* action was more effective) or were only moderate (or short in time) deviations.

In this case, you've got the dominant action having an advantage for a long time, which implies that the game has a sort of "natural wall" to it.

That behavior *does* shows up in both the "progressive (learning) defense" model and the "player exhaustion" model - if you look here, the stable equilibrium there is exactly that kind of "wall".

Hey Brian,

Great post. I have just a few comments.

You are using yards per play as your measure of efficiency, but we all know that there is more to the efficiency of a play than just the number of yards it gains. Ultimately, the efficiency of a play is the amount to which it increases your win expectation. To that end, I feel that we need to compare runs vs. passes by looking at the following attributes of a play:

a. The potential for a turnover. I know that league interceptions have been going down, but so have fumble rates (read that from a reputable source). But is one going down more than the other? Your YPC doesn't include fumbles, while the YPP includes INT. Thus, it is likely that running efficiency is actually increasing a bit. For that matter, how have fumbles on passing plays changed? Are strip-sacks more or less prevalent? How about receiver fumbles?

b. The standard deviation of yards gained. Are running plays more predictable? We know that passing completion % has gone up recently, which suggests it's decreasing its standard deviation; but has running also become a more (or perhaps less) predictable play?

c. The last thing is somewhat esoteric and I have no concrete suggestions for how to test this, but I'll just put this out there: I've heard countless people talk about the value of "shortening" a game. That is, using the run to chew up clock and limit the amount of possessions and available time for the opposing team, thus constricting the other team's number of plays and, later in the game, their decision matrix. So you may say that with a certain lead, and at a certain point in the game, running is more efficient than the actual yardage metrics will show, becaue of the guarenteed running of clock. Obviously, you aren't going to go all run after you get a 14 point lead with 5:00 left in the 2nd quarter. But it maybe that it's in your advantage to skew the run:pass ratio as the game marches on, to shorten the opportunity for your opponent to come back.

Now, as for how the above could effect run/pass balance: what if the increase in pass efficiency is allowing teams to build sustainable leads EARLIER and MORE OFTEN than before? With bigger leads earlier in games, perhaps teams are shifting to a heavier run attack as game time passes.

Sunpar-Yes, those things can be accounted for. See some of the other articles linked to above in the main post.

Pat-That's absurd. Players didn't get exhausted in the 70s? Coaches didn't 'learn' in the 60s?

You are trying too hard.

Heh, guess I could have saved time then by clicking through (just got linked to this blog, I haven't read most of your work).

Pat-I've reviewed that article again. You've quite certainly created a strawman, two of them actually. You arbitrarily constructed non-linear utility curves with absolutely no basis in empirical fact. You've literally dreamed them up.

Everyone agrees that the very premise of minimax theory is the existence of linear utility functions. In my model, as long as one considers every net point as equally valuable as another (2 points is twice as good as 1 point), then linearity holds. Further, a point scored while "learning" is equally valuable as one scored later.

As you may be aware, I was the one who pointed this out in my criticism of the Levitt-Kovash study. To overcome this problem, only situations where the score is close and time is not yet a factor are considered.

By the way, do cornerbacks get winded too?

I ran a few numbers on play calling tendencies and there are clear (and expected) patterns by quarter.

The numbers below are from the 2007 play-by-play data. It show the percentage of the time that a pass play (P) follows a pass, a rush (R), a penalty (Pen), or some other play (O) (such as kickoff or punt). The data are sorted by team and time, so it includes the start of a new series compared to the end of the last series (rather than comparing it to the last play of the other team. This also means that the end of one quarter in one game will be be followed by the beginning of the same quart the next week -- but accounting for that was too much work at this point.)

In a nutshell:

* Q1 & Q3: teams definitely tend to alternate

* Q2: there is no clear pattern

* Q4: teams tend to repeat the same play type.

Q1

__________O_____P___Pen_____R

P______13.47__34.97__5.61__45.94

R______16.06__41.51__5.63__36.80

Q2

__________O_____P___Pen_____R

P______10.93__45.09__5.48__38.50

R______14.84__43.98__5.26__35.92

Q3

__________O_____P___Pen_____R

P______12.79__38.52__5.40__43.30

R______15.79__43.11__4.63__36.48

Q4

__________O_____P___Pen_____R

P______10.92__52.20__5.58__31.30

R______11.42__37.81__4.76__46.01

Q5

__________O_____P___Pen_____R

P______14.29__36.51__4.76__44.44

R______13.13__26.26__4.04__56.57

Obviously there is more analysis that could be done --- looking at the data by team, by score, by yards to go ....

There is more to playcalling than simply maximizing the yards per play average. Running plays specifically are useful in running down the clock, reducing the risk of turnovers, wearing down the defense, etc. So it makes sense for coaches to call these plays in many circumstances, knowing full well that they are sacrificing yardage for some other benefit.

Yes. That is well understood, and that's what was meant by, "Without detailed play-by-play data, we can't rely on advanced metrics like Expected Points Added (EPA). Instead, simple efficiency will have to do."

Besides, those circumstances in which yardage is less important than time or other considerations will exist across all eras of the NFL.

Someone finally mentioned the clock! Shouldn't all this data be analyzed not just by how many points or yards runs or passes generate but how many points or yards they restrict from the opponents by consuming time!? It seems to me that that way a more balanced idea of the usefulness of Run vs Pass could be understood. Time is too important a factor to be left out of the equation as, unlike say Chess (my favorite game), it's not equal for both sides. Less time on the field = less chances to score and therefore less overall points generated. So a Run play would generate less over all points scored per attempt but more opponent's points restricted per play, or something like that... What do you think? (maybe you could find a mathematical expression of "the overall time of possession divided by scoring drives per game" and translate that into points restricted by running plays, or something, just thinking off the top of my head here...) Am I off base here!?

One more comment, and I realize this seems too ethereal a thing to put into a stat analysis but there is the factor of fatigue. Pass Blocking and Run Blocking are two completely different tasks that demand different levels of energy from the player. Similarly Run Defense and Pass Rush do too. If running the ball fatigues your opponents more (the corollary benefit of consuming time is keeping the opponent's defense on the field longer) it will have a corresponding effect on 3rd and 4th quarter effectiveness. On paper Ali never beats Forman but by using the fatigue factor Ali defeats Forman easily... How can fatigue be factored into the analysis of run vs pass on a statistical level?? Any suggestions? (p.s. - many wide receivers rest on run plays, even though they should be blocking... and running backs catch their breath pass blocking too... though how you'd factor this in is hard to say in a statistical world but in real football fatigue is a factor in how and why plays are chosen.)

Yes. The clock, score, and other aspects of the situation is considered in my Win Probability model. Unfortunately, there isn't digital play by play data available to apply the model before 2000.

The clock and score certainly matter in any single situation, but over the course of an entire season or many seasons, those considerations even out. In other words, each season will feature roughly equivalent numbers of plays in various situations.

Yes they have “evened out” over the years because no coach has been silly enough to abandon the run in favor of the "all pass play" suggestions mentioned a few times above (Don Coryell comes to mind as someone who found this out the hard way, stats people always liked to mention how "bad" the Chargers’ Defenses were missing the simple point that the pass dominant offense used less time and kept the Chargers’ Defense on the field more thus fatiguing them and making them less effective.) I guess my response is fueled by this "analysis of stats in a vacuum" style thinking that permeates so many "stats" discussions and drives me crazy. The stats that "even out" due so because coaches "in the know" don't allow them to get out of hand by ignoring important real life factors like time and fatigue... If I'm missing your point completely I apologize I haven't analyzed your Win Probability model yet so I don't know how much of this you've factored in elsewhere...

Is it possible that the substantial decline in Pass YPA in the 1960s and 70s is due to a dramatic increase in the number of starting QBs? In 1959 there only 12 starting QBs. By 1978 there were 28 starting QBs. The main reason for this is the inclusion of 10 AFL teams plus a few more NFL expansion teams. As you add more teams the number of talented QBs does not automatically expand, so it just may be that many previous backups were suddenly thrust into starting positions.

A simple test would be to chart the Pass YPA for the top 12 QBs from 1959 to 1978 to see if this nullifies the downturn.

The numbers in aggregate are interesting, but not revelatory. Increasing short-yardage running situations will bring down the average yards per rushing attempt, but does not speak about the success of a running play. Yes, not every "running down" will include a run, but I imagine that runs face a steeper yardage penalty than a pass in those situations.

A more honest evaluation here is the expected YPC/YPA on 1st and 10, or an analysis of short-yardage running plays.

Running the ball has other advantages.

First, running the ball effectively uses up the play clock, and generally "shortens the game" in terms of the total number of possessions during the game for each team.

A great example of this is where the New York Giants, chiefly a running team, defeated the Buffalo Bills, an aerial power, in Super Bowl XXV.

Another important point to make is that shortening the game by running the clock down also gives the defense a chance to rest while the offense is on the field.

Conversely, in this scenario, the opposing defense is not allowed a chance to rest, and is worn down by the running team's offensive line.

To highlight this point, consider that the teams generally known as "running teams" generally have the most effective defenses.

(The Chicago Bears in the 1980's, the New York Giants in the 1990's, the Baltimore Ravens in the early 2000's, and the Pittsburgh Steelers as examples)

Simply put, a defense that is built to be on the field for a below-average number of possessions per game can be built around athletes who have more "quick burst" and power as opposed to more endurance athletes required by passing teams (white muscle fiber vs red muscle fiber).

What also would be interesting to look at is if there's a major penalty differential in running vs. passing. For one, I imagine that, on average, there are more holding calls on pass plays. On the flip slide, do unnecessary roughness calls, pass interference, defensive holding calls account for any statistically significant benefit? This is just purely speculation, but isn't the general wisdom that NFL penalties are weighted to the pass game vs. run game?

Passing teams tend to be more successful because the QB are in control.

Really interesting post here...

Obviously the Mel Blount rules changed the passing game forever.

But there have been many small changes over the years that I think have led to offenses creating more points. People like points in general, few fans love a 3-0 game (I'm one).

However, not all rule changes are created equal. And some will have smaller steady impacts. For example the new rules regarding hitting defenseless receivers will probably lead to a few more caught passes and maybe even some more YAC when a tackle is missed that maý have killed the receiver before.

And all these small changes correlate into increased passing prowess as time goes on.

Numerically it makes sense to pass on every play since you are at an advantage on all plays by spreading the field and limiting the amount of available blitzes the OL need to pick up.

However this will likely result in smart defensive coordinators blitzing everyone in an attempt to remove the starting QB from the game. In fact this would be the most proficient way to play defense. Even if you give up a TD, injuring the QB by sending all 11 on the first pass play of the game would result in the opponent, particularly if the opponent has a star QB, scoring far fewer points than if yo played a conventional defense.

If i were coaching a team with a limited QB, i would make it know that more than 20 passes per game will result likely in QB injury.

There will forever be intangibles, because human beings play the game. Football intelligence, body type, athleticism, preparedness, and emotional state on a particular day/play - lots of things influence execution. I have not seen any references to what happens after a play is called and before it has ended. Generalized statistics include results by highly effective and highly ineffective players and coaches - all blended together into an homogenized puree. This data seems to assume that all players are equal. The best play callers and the best play makers seem to be those who are able to adapt most effectively to what the other team is doing and to outperform them in the field. Tendencies really should only be applied to the play calling of particular coaches and the trends in execution of particular players.

Ian you are right. Coaching is done with the mind not stats. Stats can help explain things. But too much importance is placed on YPC, YPA, etc, etc. As you state there is the variance of outcome, and situation, and a host of other variables, that dictate the outcome of a play, drive, game and season. What you are saying is exactly what all DCs would say. I have to stop the run to rush the pass. That's the philosophy. And it's based on the variance outcome you explained. And one more, the variance of the Ds ability to reacte to the play coming at them. The higher % the chancce for a pass/run play exists the easier the play is to defend. In short if the D doesn't keep the run around 4 YPC they will always be guessing run or pass. And on another note it is only a matter of time before colleges and nfl start producing the # of quantity of CBs needed to defend the kind of offensive attacks we are seeing. Somewhere along the line as this trend continues and grows. SOme coach will say, you know everyone is trying to run these pass-prolific offenses. I'm going to carve my nitch out by being the first one to focus on stopping them. See it only takes a Tony Dungy to stop a Bill Walsh, and stop current pass trends. The game has been back and forth. From the proto-WCO of Paul Brown, to the 4-3 of Laundry, to the WCO of Walsh, to the Buddy Ryans 46 D and it's 4-3 imitators, to the 2nd gen "jumbo" WCO's of Walsh's students. To Dungy's Tampa 2, which met Martz' Greatest Show on Turf, which met Marvin Lewis' multiple look D, and Dick Lebeau's zone blitz, and onto Belichick's pro spread offense. This has been the NFL for years. Somebody innovates and others immediately immitate. Then the other side adapts, and the process repeats itself. There is just not a dominant D answer to the current spread offenses. At some point more teams will figure out that over sized SS and under sized WILL LBs are the answer to man coverage on TEs like Grownkowski. SOme teams already have. But not many have them guys on their roster right now. But every offseason gives all the defensive minds months to pour over tape, and try to brain storm a new strategy. And as long as Ds continue to have little answer for what the offenses are doing, the offenses won't change much. And all it will take is one teams crew coming up with an answer and the trend begins to swing back.

Teams continue to run because it eats up the clock. It's about ball and time control. With the ball in your hands and time ticking down who is statistically likely to score, offense or defense. If passing is so efficient then I need only go to it when the yards are needed. The negatives of rushing are fumble and loss of yards only.

the negatives of passing are interceptions, sacks (-gain), incomplete pass(clock stopping and 0yards), and fumbles.

With passing vs rushing though the gain is nearly doubled, the negatives and possibility for turnover is also doubled.

Naturally it would make sense for a defense to play the pass with twice the chance for turnovers in ones favor.

BUT, how much is really gained if those negatives exist regardless of defensive scheme. The fact the offense is calling a pass play increases the defensive chance for turnover in their favor twofold all on its own.

Now by defensively playing gap control and rushing schemes, it automatically limits the offenses rushing positives, and increases the pressure on QB's to make faster, quality, reads. Not to mention the lower need for depth and to field exceptionally skilled players in Defensive Back Positions. It is far easier to find and field a run-stopping or pass rushing LB/DL specialist than it is find a quality cover or Shutdown DB let alone fielding two or more for more pass oriented coverage.

And as stated before if passing is so efficient one should only use it when needed because along with the degradation of efficiency with increased use there are twice as many negative outcomes which invariably have greater impact on the success of drives and scoring than the Yards Gained per Pass.

So it is only natural for a defense to run blitzing or run stopping packages versus cover schemes. But thats just my argument as to why Defenses preferably focus on the run over pass.

There are too many variables to ever be able to definitely say that any level of offensive balance is optimized. But I can say that (to use Madden as a simulator) when you know your opponent is going to pass pratically all the time it is much easier to choose a defense, but unless you have a good pass rush the QB will always have the advantage. If you take the 2012 Super Bowl Giants as an example, their success on defense (specific to the last 2 games of the regualar season and the playoffs) was due to a combination of a consistent pass rush (without blitzing often) and being able to have a hybrid SS/LB on the field and not get crushed on running plays.

But the other issue is that even if you know exactly what the offense is going to do doesn't mean you can stop it, it only makes it more likely you will. But I agree with the idea of reaching a Nash equilibrium and not having both play types produce equal value. It is just the ratio that makes the avg play value for all plays the highest, which in today's NFL definitely favors the pass. But remember football is situtational not theoretical, if you have 3 and 2 maybe a pass would net the highest average gain, but a rush represents a highly likelihood fo getting a first down. Sometimes it doesn't make sense to get the most possible yards since you only have a limited number of attempts.

I don't think the NFL is stupid. I think that the way the game is officiated makes it so that the only logical way a defense can slow down a good passing attack is getting the quarterback on the ground. I passed statistics but you probably know a lot more about the subject than I do but all you suggest is shifting focus to stopping passing attacks. Like how? Dropping 8 into coverage, exotic blit packages, more aggressive man coverage?

I'm more curious about the impact of an efficient run has on the opponents likelihood to successfully pressure a quarterback on the following play. I feel like the reason teams still run the ball at the clip they do is to prevent defensive lineman from shifting their entire focus on stopping the pass.

Also, is there a correlation between the distance for a down being longer and the likelihood of the defense successfully generating pressure? while you may gain more yards in total on 1st and 10 passing, you'll still have missed attempts and I'm curious how the odds of your quarterback getting knocked around change between a 2nd and 6 and a 2nd and 10

I don't think the run sets up the pass anymore, but it very well may help to protect a team's most valuable asset

"With passing vs rushing though the gain is nearly doubled, the negatives and possibility for turnover is also doubled."

that ignores the likelihood that these events occur. I feel like passing is substantially more than twice as likely to result in a turnover as I can't help but figure a quarterback and receiver would generally have a higher fumble rate than a running back and that interception rates would be a lot higher than any of their fumble rates.

Is this a good summary? : Passing efficiency has gone up more than running efficiency but teams are hardly passing more. Therefore their mix is suboptimal.

I don't see how the conclusion follows. It could be that teams were passing too much beforehand and now it is at a good level.

I think your graphs should read left to right.

Its funny to read these "educated" posts from some guy in Germany about the dominance of the passing game. The Seahawks 2013, 2014 and soon their 2015 SB runs will continue to prove the value of a strong running game, and using that valuable cap space to prop up a defense to stunt the opposition.

Anyone who saw Manning and the Brocos lose a 5 TD lead at half time to the Patriots in 2013 knows the value of a running game ISN'T just the ability to move the line of scrimmage... it's also the ability to eat the clock once you get the lead.

Any team who can eat clock when they're ahead, is a team the opponent can't catch up to. The run game is strongest when paired with a strong defense, as it makes the both teams possessions count drop (less actual game time) and keeps the defense fresher than a big-gunning passing competition when corner backs and safeties get gassed by the 3rd quarter.

"I think your graphs should read left to right."

Amen.